I have stolen this catchy title from the eminently likeable Mike Cladingbowl, OFSTED’s Director of Schools. You heard me right – top inspector praised for his sage words about teaching and learning. Here they are for your delectation:

“What about teachers’ subject knowledge, the children’s sense of routine, the ability to turn direction mid-sentence, a common sense approach to differentiation, the sense of humour, the infectiousness of the explanation? I see too little of this kind of comment about teaching.”

Ah, he knows what he is talking about I hear you say. Stripped of corporate jargon, he manages to describe teaching in a way that the vast bulk of OFSTED reports fail to do: he describes the act of teaching with wisdom and sensitive insight. Common sense and humour; routine balanced with flexibility, and more. Of course, this degree of complexity described goes beyond the easy response of a nice, neat data capture. Cladingbowl indirectly encapsulates why lesson observation data is deeply flawed.The craft is so subtle, and often invisible, to all but the most skilled observers.

For too long, it has been the fearful response of schools to OFSTED pronouncements that has curdled our milk of classroom practice. I have criticised before the pervasive whispers of ‘talk less teaching‘, with the attendant professional development courses that litter the teacher-sphere.

Here, alongside Mike Cladingbowl, I want to reject the curdled notion of ‘talk less teaching‘ and herald the power of ‘talk better teaching‘.

Few areas of pedagogy have the ‘low effort, high impact‘ capacity of teacher explanations. They are the glue that holds learning together. In response to a TIMMS study of a maths teaching, Dylan Wiliam noted that in US classrooms, which are similar to our UK classrooms, there were 8 teacher words for every students word whereas in Hong Kong the ratio for teachers was double that of US teachers. He went on to state:

“Obviously, speaking is good for the speaker, but when you have whole class discussions, a lot of the time, what students are listening to is other students, who don’t generally know as much about the topic as the teacher. When you look at things from this perspective, it is easy to see why teacher talk is so important.”

It is a simple, but potent truth. Wiliam is not saying students should be struck dumb into silence throughout their lessons. An engaging dialogue between their peers can help students move their understanding forward, but, once more, it is the teacher who must lead and decipher what peer feedback is useful and when to intervene as the expert. As Graham Nuthall’s brilliant research found, student feedback given to one another is very often flawed. Teachers therefore need to confidently assert their expertise and lead from the front.

Too many teachers have had their confidence to plant their feet in the centre of the room and give a great explanation neutered. Notions (or interpretations of supposed OFSTED dictums) of pace, independent learning and ‘talk less teaching‘ have pushed some teachers towards relegating themselves to the side and not the centre. We need to replenish teacher confidence and ignore the flawed notion of ‘talk less teaching‘ and focus on ‘talk better teaching‘.

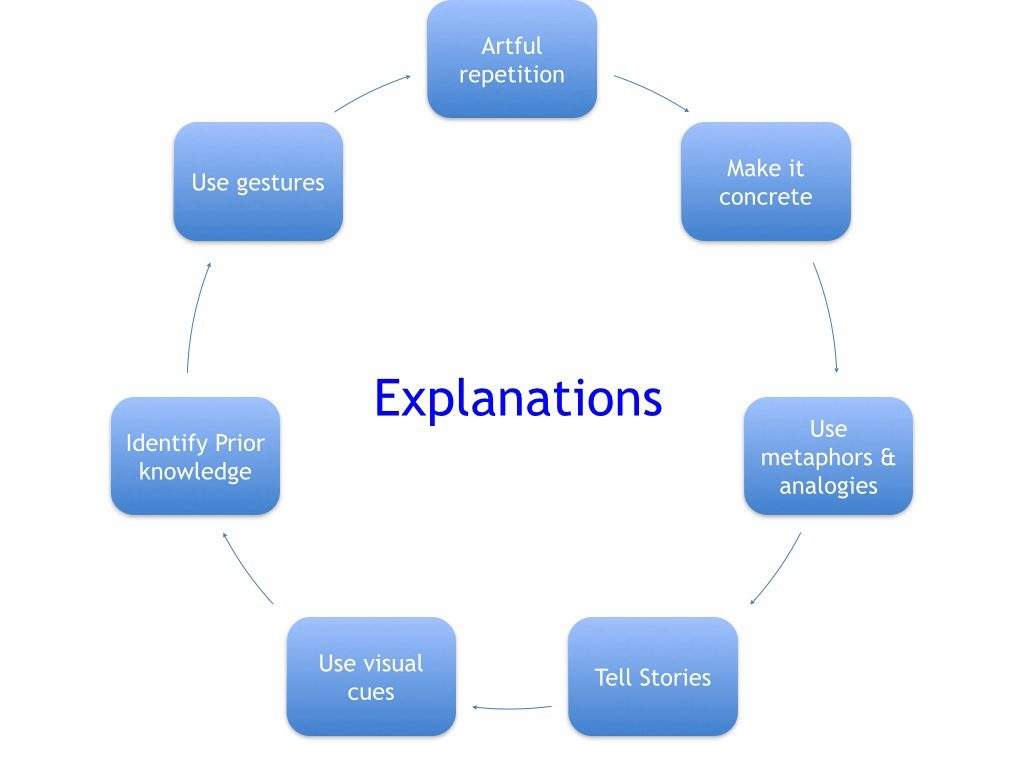

With that in mind, I have designed what I hope is a helpful explanation diagram – a guide to the key components of a great explanation:

My ‘Explanations: Top Ten Tips‘ elaborates in detail on most of the steps of my diagram – see here.

Recently, at the NTEN ResearchEd event at Huntington School, I talked about the importance of gesture and I talked through each element of my diagram. See the video here, with the explanation focus beginning at around the 27 minute mark:

}

We should take the time to construct infectious explanations safe in the confident knowledge that ‘talk less teaching‘ is a wholly flawed notion.

It is time to focus on ‘talk better teaching‘ and infectious explanations.

Useful related reading:

There have been some great blogs written on effective explanations and I have endeavoured to link them here.

This Zoe Elder blog has a great series of tips for effective explanations, with a very useful explanation observation tool – see here.

The excellent @Turnford blog has written a perceptive post on ‘Great Teacher Talk’ (I sourced the Dylan Wiliam quote from here) – see here.

Tom Boulter has written a perceptive blog on the ‘Top Five Ways to Explain…Badly’ – see here.

Undoubtedly, my favourite chapter of my book for English teachers is on explanations and teacher talk. I think it is very useful. My book, ‘Teach Now! English: Becoming a Great English Teacher’ is available here.

Unless I’m missing the point. While I thought I did focus on “talk better teaching” some years ago, I was criticised for talking too much, by line managers (who had been on a half day training course) and advisers, (who had been on a two day training course), even though what I was saying to pupils I thought, was relevant and significant for their knowledge, understanding and progress.

At the time my argument was, that pupils talking amongst themselves may not have know what they were talking about and classrooms became an extension of break-time. Without the initial input from the teacher, pupil group work was pointless, however, I was encouraged to continue with this teaching and learning “policy” (diktat). I’m sure I’m missing the point.

Your situation sounds all too common. The tide appears to have turned, or at least is turning, away from such short-sighted ‘policy’.

Reading Nuthall back in the mid noughties, what I never got from that book or any of the other writings was any understanding that the teacher had to stop talking. The teacher had to start listening, engage more in the learning conversations taking place in the class, adjust practice such that pressure was put on the learner to make their mind up, make choices, take risks and so forth. 40 years in the independent sector has genuinely hidden from my view the extraordinary pressures the Ofsted lesson observation has placed on state school staff. Actually hidden is not quite right. I remember participating in a day-long training session for GTP mentors 10 years ago, when a video was used to show how a good teacher could become an outstanding one. 50 delegates, 25 from each sector were present and we split equally down the divide after seeing both videos, because it was quite obvious to us all that there was more interesting learning and responsibility transfer taking place in the good lesson rather than the great lesson, but also clear that some children were not making ‘expected’ progress in the good lesson.

It was on castle construction, and there was no right answer!

Great post.

There’s lots of reasons for us to become, once again, central characters in the theatre of our own teaching.

Subject expertise, when allied to pedagogical excellence, is an accelerator of learning. For numerous reasons. Lots of those you post above, and you are absolutley right – that we talk and how we talk are both key.

In addition to all the good stuff above, a big issue with self-directed learning is that, even at university level, student’s self awareness of error, self-correction mechanisms, and learning strategeis are often less than perfect. Students; are not necessarily the best candidtaes for decioding what to learn and how to learn, and student’s assessments of what they feel they have learned, and how they learn best often fail to correlate with the reality.

I think of it less as sage on the stage with students as an audience, and more as a theatre in which all the participants partake in a carefully engineered experience. The authorial power shifts, with prior knolwedge of the subject, with the level of confidence different participants have, with the level of mastery students display, and with the level of metacognition and critical/learning straegies students evolve.

If I might ask – could I take your graphic and play with it?

Please do.

Improving teacher discourse such that great explanation is given is a benefit to classroom practice – it is amazing is it not how little time is given to this in planned CPD normally. Having your video extracts from the NTEN conference is really useful. Since you give the example of Maths in your blog, I share with you Dan Meyer’s stuff from the NRICH conference in Cambridge last year. http://nrich.maths.org/9904

He has also generated a spreadsheet of such ideas, so that teachers can use this approach quite broadly and across the age rage. http://www.watsonmath.com/2012/04/24/spreadsheet-of-dan-meyers-tasks-in-three-acts/

Now I am a scientists rather than Mathematician, and in recent years very much focussed on ICT, use of Cloud, WIFI and Chromebooks. The best work we generate seems to be from Meyer’s direction – keeping the questions with the learner, apparently slimming the curriculum so there is more time for this approach. Just seen some of our year 9 projects (that have replaced their summer exams) with the Victorians at the heart of the studies and the best are breathtakingly good. The weakest (1) worthy of an exclusion, but then that would be that way whatever the approach!

Cheers James – I will take a look at the Meyer stuff.

Alex, couldn’t agree more. Teachers being encouraged to inhabit the corners of the lesson instead of being the expert in the centre who can show their passion for their subject is a joke. An engaging, sincere, humorous speaker can inspire kids and become a true role model. Am new to this blog world, but learning. Hope this gets to you across York. Steve at Canon Lee

Cheers Steve. Surely we’ll meet at some point, given we are down the road!

Came looking for your NRocks slide presentation from the first year and found this instead – brilliant – thanks Alex.

I love the idea that we as teachers need to time to ‘talk better’ and that this is something that can be explicitly developed rather than left to happen chance. Brilliant.

Thanks Bec.

Pingback: Excellent Explanations (Part 1) – How then should we teach?

Pingback: 6 Features of Excellent Explanations – How then should we teach?