If you can write well, you can succeed in school. But the impact of being unable to write with confidence can be crippling, in the classroom, as well as far beyond the school gates.

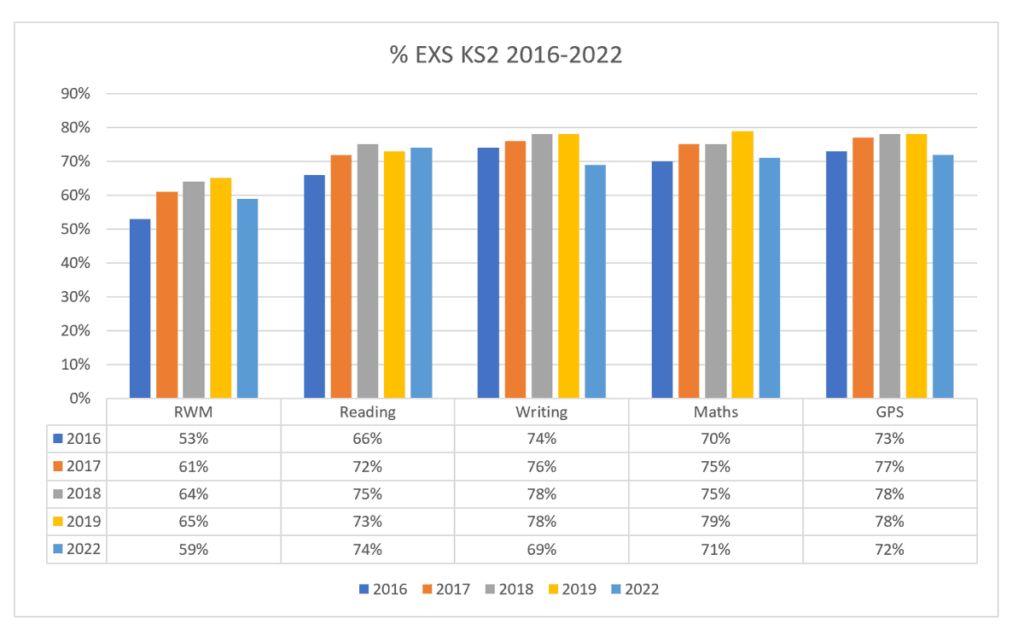

The recent White Paper on ‘levelling up’ education by the government, predictably attempts to address writing and the age-old ‘3Rs’. By 2030, the government wants the number of primary school children achieving the “expected standard in reading, writing and maths” to reach 90%.

Despite widespread recognition of the importance of writing though, it is routinely the ‘Neglected R’ when compared to reading and a(r)ithmetic (maths).

Many teachers don’t feel confident teaching writing, it doesn’t feature so highly in school inspections, nor does it feature so ubiquitously as a priority in school improvement planning. This relative ‘neglect‘ means it doesn’t have the cottage industry of supporting products, apps, and intervention programmes that accompany the likes of reading.

Has writing got worse as a result of the pandemic?

Do these plummeting results reflect the unique impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and partial school closures on writing development? What can we realistically infer from this teacher assessment (usually more generous than standardised testing)? Is it an anomaly, or it is representative of a wider issue with pupils’ writing development in schools?

We can speculate that the conditions of the pandemic made it hard to support and sustain pupils’ writing development. Reading at home during partial school closures, along with a legion of maths apps, may have been easy to deliver than the complex act of improving writing.

There is a peculiar magic when it comes to developing writing in the classroom that was missed. Pupils get ample feedback on drafting and crafting writing. Complex writing tasks are broken into small steps and modelled. Pupils of all ages hear the examples of peers, often writing collaboratively or collectively, and have a live audience to ensure that editing (correcting errors) and revising their writing is completed with due care and attention.

Additionally, many parents may have lacked the confidence to support their children with writing. With my son, I quickly recognised his handwriting had been affected by reduced practice, never mind spelling, grammar, planning extended writing, and more.

What do we need to do about writing?

We should not have any knee-jerk reactions to SATs outcomes, but we should be conscious that developing writing has always been tricky and too many pupils have failed to develop their writing skills.

If we live in a country where functional illiteracy affects millions of families – before the corrosive impact of the pandemic – then we need to pay equal attention to all of the 3Rs. Indeed, writing may even matter more right now.

So, what do we need to do about it?

Across the world of education, there have been calls for a ‘writing revolution’ and an awareness that new teachers (and old) can struggle with the teaching of writing. Research indicates it may lack the requisite curriculum time and training for schoolteachers.

For 90% of pupils to master such a complex skill requires sustained support and expert teaching. It requires policy support and thorough planning. If teachers struggle with teaching writing, then training and sustained focus on professional development will be key. From early writing – to disciplinary writing in secondary school subjects, as pupils develop to ‘write to learn’ – there needs to be a roadmap for teacher knowledge and practice.

There is likely a need to revisit national assessments for writing. Does the GPS (Grammar, Punctuation and Spelling) test in year 6 translate to better writing? Is writing assessed and developed well into secondary school?

Beyond testing and assessment, do we need to focus school improvement attention on writing progression in the curriculum? Does handwriting need a higher profile? Can we support spelling beyond weekly testing? Can we explicitly teach the writing process more consistently and successfully?

Do we need to revisit our curriculum intent when it comes to improving ‘writing like a historian‘ or a scientist, and more (the stuff of ‘disciplinary literacy’, twinned with subject expertise)? As an ex-secondary school teacher, I may even offer the provocation that writing is routinely neglected – based largely on a lack of awareness and intent to address the issue.

Aiming for 90% of pupils leaving primary school as strong writers may be a laudable aim, but it will we not get anywhere near if writing continues to be the ‘Neglected R‘.

Comments