What do you assume are the skills of a successful art and design pupil? Perhaps you consider an understanding of perspective and proportion, colour and tone, or knowledge of different media, all deployed with creativity. We know pupils must do some writing in art and design, but it doesn’t *really* matter so much, right?

Though we associate art and design with expression in paint and similar, or the production of creative products, there is a significant amount of writing required to succeed in the classroom. You find it in researching products or painting, annotating, evaluating, and more.

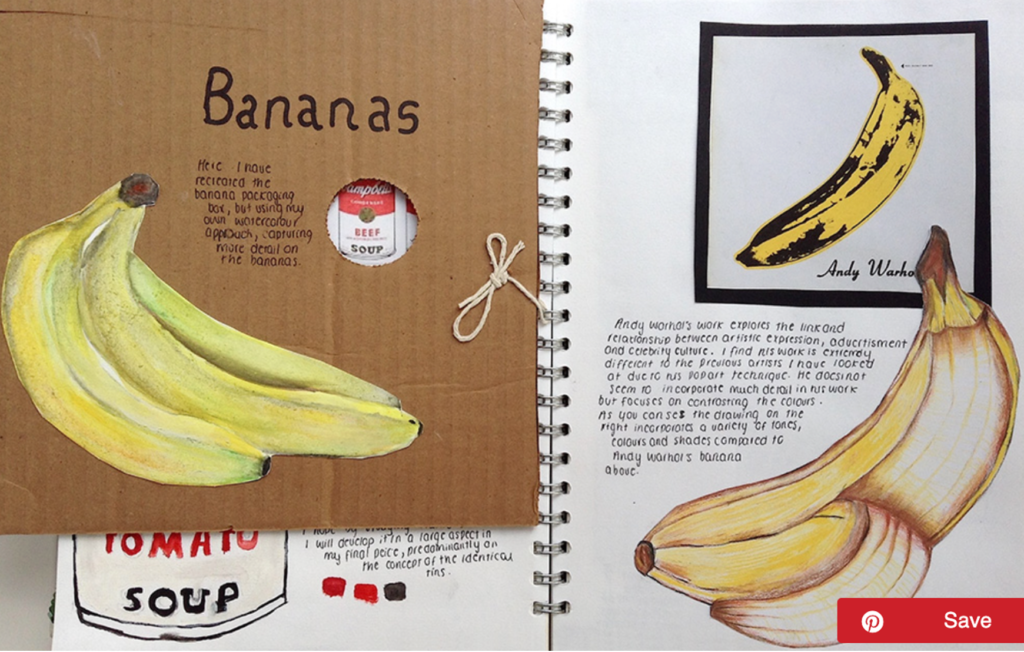

Consider this question: what writing was undertaken in the production of this piece of art planning?

This young and skilled artist is also very literate. Likely they read lots about Andy Warhol and made notes to record those insights, processing and distilling their understanding to inform their own artistic moves. There is the visual of Warhol’s banana image, but in the writing there is the vital recognition of the links between style, medium, and Warhol’s pastiche of advertisements.

For pupils’ portfolios and projects at secondary school, the ability to annotate your plans and finished projects is vital. Not only that, but pupils are also expected to evaluate their ideas in writing.

A near-hidden reality is that pupils need to do a lot of research, reading and writing to interpret the ideas of great artists or other products designers. You could fairly argue that you could read up on Abstract Expressionism, but not have the skill to paint with mastery of brushstrokes or colour. And yet, there would be few advanced qualifications or professional roles that didn’t assume the knowledge and skill of writing about research or products that attending the creative acts of design or art.

Practical strategies to improve writing in art and design

Ample research evidence indicates that writing about you read improves your comprehension and memory of the reading material. Making judicious and well organised notes is a skill that is too often assumed.

It is helpful then to support novice pupils with organising their notes and insights via graphic organisers. From relations diagrams to concept maps or Venn diagrams, different graphic organisers help communicate different ideas (see Oli Cav’s brilliant doc on ‘Organising Graphic Organisers’ HERE).

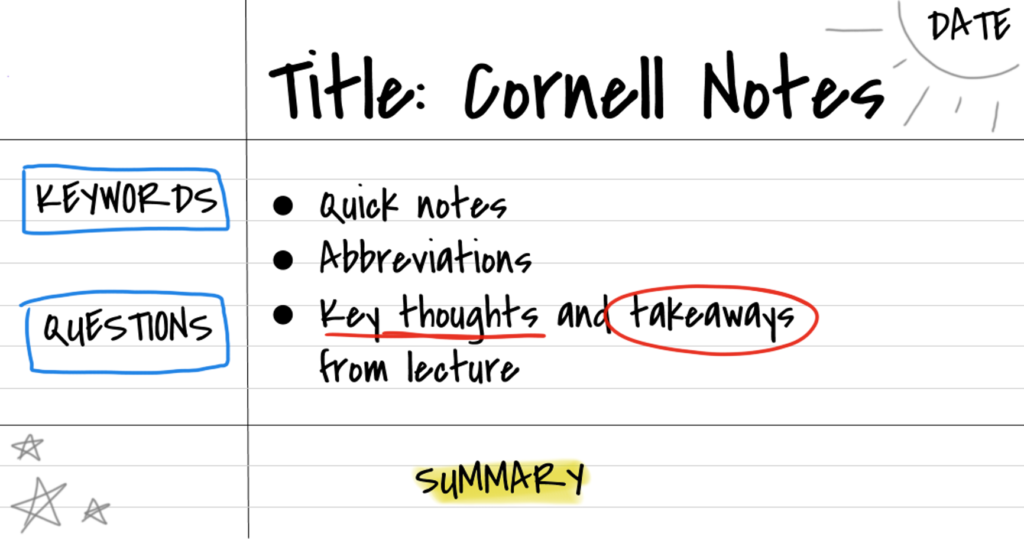

A popular approach to organising notes across different subject disciplines is the Cornell Note-taking Method:

The Cornell method is useful for a variety of reasons. First, it ensures we explicitly teach pupils that note-taking requires some hard thinking and purposeful organisation. Being prompted to note key vocabulary and questions to consider ensures pupils are being more precise about the information they need to use and retrieve. Additionally, summarising helps ensure pupils elaborate and attempt to synthesise their knowledge.

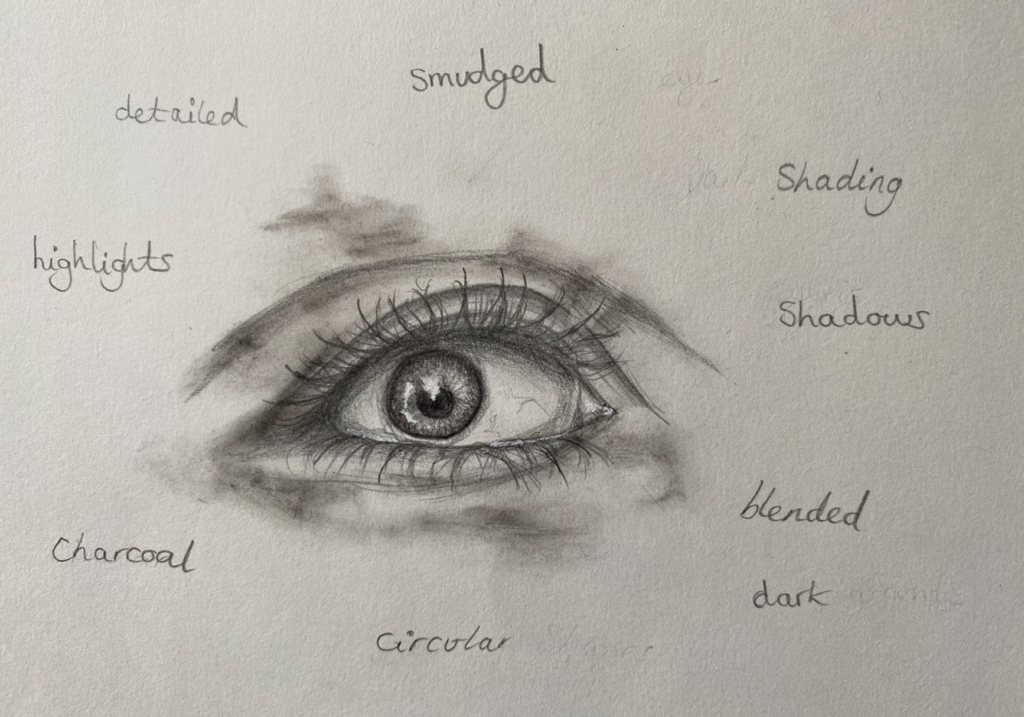

Another area of writing that is too often assumed to be done with understanding by novice pupils is art and design annotation. We all know a spattering of key words is broadly the approach, but if the annotation is to be purposeful, it is an opportunity to record the specialist vocabulary of artistic technique and meaning that we want pupils to remember and use habitually.

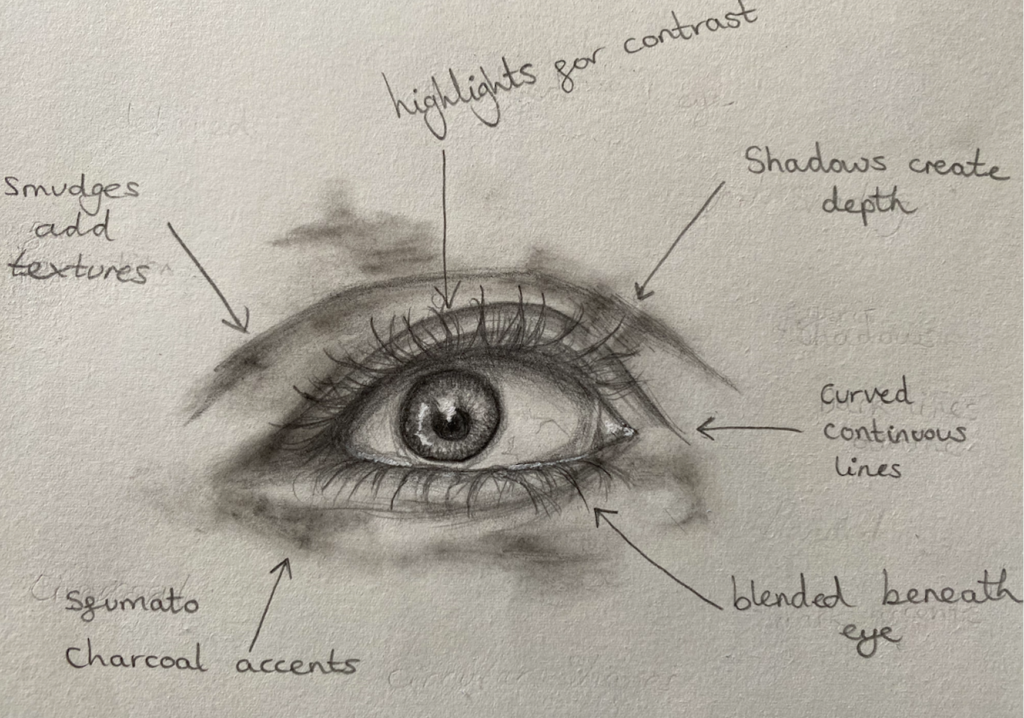

As such, a small prompt to move from single-word annotations to ‘Three-word annotations’ can enhance pupils use of precise subject terminology and makes for accurate, skilled annotation. The exam specification may deem single word annotations adequate, but more precise, detailed annotations can help develop knowledge and understanding that is better than adequate and goes beyond the narrow boundaries of the specification.

Compare this before and after, from single word annotations, to scaffolded ‘Three word annotations’:

The more precise and detailed annotations allow the pupil to exhibit their understanding, but also it allows for more targeted, purposeful teacher feedback too (for instance, for the next project, you could fairly ask the pupil to concentrate on the use of ‘shadows and charcoal accents’). When you add the specialist subject language consistently into note-making and annotations you support pupils to habitually use accurate and precise disciplinary language. They better write, talk and communicate like artists and designers.

Such writing habits obviously ensure that pupils’ writing for design coursework or examinations are more likely to use apt academic terminology. It is common to use writing scaffolds for such projects. For instance, with a Year 7 design technology new product brief, you can begin with the cluster, ‘First…furthermore…so that…’ to introduce your product, followed by a cluster to focus in on one specific element of the product development, such as ‘Due to…for this reason…notably…’.

Additionally, ‘So that sentences’ stand out as a manageable and meaningful scaffold to use regularly in art and design. Pupils take a technique in an evaluative sentence and ‘so that’ prompts their purposeful explanation:

I used [Art technique] so that .

I used the sfumato technique for the face so that the portrait appeared soft and youthful in contrast to the harsh, jagged lines of the busy street background.

Structuring more extended writing can be scaffolded at the whole text level too. For instance, in art, Rod Taylor’s ‘Content, Form, Process, Mood’ structure can offer a useful set of prompts to scaffold the written analysis of any work of art.

Too often, we deem artistic creativity as a rare gift bestowed on a lucky few. But every genius artist and designer has undertaken a long path of practice and careful, incremental improvement. Lots of drawing, planning, moulding, creating, painting, planning, evaluating. Success in art and design is borne out of these small improvements, practised week after week. Writing too is woven through this lengthy pursuit of art and design excellence – with explicit attention on research, annotation, note-taking, and more.

Does writing *really* matter in art and design? Yes… yes it does.

Related reading:

- The strategies from this blog are drawn from my book, ‘Closing the Writing Gap‘. You can grab a copy on Amazon HERE or from Routledge HERE.

- This blog describes ‘disciplinary writing‘. To find out more about the importance of ‘disciplinary literacy‘ more broadly, read the EEF guidance report on ‘Improving Literacy in Secondary Schools‘ HERE.

I’ve just been sent this by a colleague. It makes for an interesting albeit frustrating read. As an art teacher, using words here, I’d like to table some of the potential blind spots, but hopefully in a way that is constructive and not perceived as overly-critical, because it’s interesting – and rare – to encounter non specialists (in art that is, not writing) to take on these themes. To begin, the choice of initial imagery is an issue, at least for many art teachers who’ll find it both familiar and off-putting. It’s the classic smudged and wonky floating eye! “The window to the soul, Sir!”. It’s a well-worn trope of art rooms, synonymous with sketchbook perfectionism and unimaginative and counter-productive ticking of assessment boxes. The (re)labelling in the image chosen is interesting, not least because you can see how they’ve rubbed out the words and re-written them. It’s not suggestive of authentic engagement with observation, processes, materials etc. but something else. But then – and here’s where art and words have the capacity to shape meaning and complicate the matter – inadvertently (ironically, ‘contemporarily’, even), the image with the arrows has the potential to be of value precisely because of how these words and image combine – the arrows coming out like extended lashes; the words labouring to add insight (mis)stating the obvious, convert the drawing into another kind of diagram. The eye looks increasingly petrified. The result is representational of so many of the issues with art assessment and how/why art students should/shouldn’t annotate work.

Perhaps it’s worth noting too the challenges (sometimes impossibility, or futility, even) of attempting to condense experiences of art into words, but also the potential here in the art room for embracing – testing out – alternative ways of doing this, in ways that might make the artist-writer and reader feel, think about, connect with the experience of art making, or artworks themselves, and how these affect, for good and bad. E.g. Limitations with available words, such as cutting/collaging best fit explanations from a newspaper; poetry; streams of consciousness; fragmented statements, made-up words … all of these can be helpful too, plus more liberating, and often more interesting. Which is not to say students shouldn’t learn how to explain their work and art-related encounters. And, of course, this needs structuring at times, of which you provide possibilities. But students do need to think critically about how and why. And teachers need to appreciate that students need time to wrestle with articulating how or why they think or feel something. Some of the words you have used here, such as ‘vital’ and ‘precise’ can be problematic. The art rooms, art sketchbooks, art works and art experiences can be open-ended and ambiguous, and whilst students can – should – be exposed to how words help to better explain art (and gain marks) we have to be careful it’s not formulaic or reductive but exposes complications and opens new possibilities.

Hi Chris, Hopefully the simple approaches shared do not at all inhibit other creative approaches to annotation – indeed I recognise the obvious limits of a few hundred words in a blog. It appears a lot of art teachers and leaders have found it useful, but I am always keen to hear what other approaches may be useful or more apt from other perspectives. I also recognise the challenges with matching assessment aims, but I do not offer easy answers. Thanks for reading, Alex