How do you teach a tricky new word, or seek to boost the word hoard of the pupils you teach?

One of the most common approaches to developing academic vocabulary is to study morphology – breaking words down into their component parts and roots. It can support the development of academic vocabulary in subjects like science that are laden with technical vocabulary, as well as building a rich networks of new word families for use across the school curriculum.

It is an approach as ancient as the Greek and Latin societies that generated so many of the words that clothe our modern-day school curriculum. New research keeps adding to the picture that this is an approach teachers should consider as part of essential classroom practice.

A small recent US study on, ‘What’s in a word? Effects of morphologically rich vocabulary instruction on writing outcomes among elementary students’ (2022), revealed that young children who were taught with a morpheme focus to thier instruction made gains with spelling and understanding word meanings, though it was less effective when judging essay writing (a much bigger challenge, where word knowledge and choices may be compromised).

The second recent study on morphology teaching, entitled ‘Growth in written academic word use in response to morphology-focused supplemental instruction’ (2022), showed that for older primary school age US pupils, they developed an increase in academic word use across two terms when given morphology instruction compared to business as usual. Interestingly, pupils who struggled with literacy didn’t make as many gains – which should give us pause.

How often do the word rich get richer, no matter our attempts? It doesn’t rule out teaching vocabulary using morphology, but we should recognise that some pupils will still struggle to develop academic vocabulary and they need our additional supports to access the curriculum. Breaking words into their component parts can simplify the complex act of getting to grips with academic language, but trialling and testing it in the crucible of the classroom will matter.

What practical approaches can mobilise morphology teaching? Here are 4 Mighty Morpheme strategies:

- Root Races (or ‘Spelling sprints’). Pupils enjoy being exposed to new word roots and making a race for generating as many words from that root as possible. Take the root ‘Magni’, meaning ‘great’. We give pupils a minute or two to generate as many words as possible (individually or in groups). Think ‘magnificent’, ‘magnanimous’, ‘magnitude’ and ‘Magna Carta’. Then, after some counting of words, we can explore their connections and meanings and create rich academic word families.

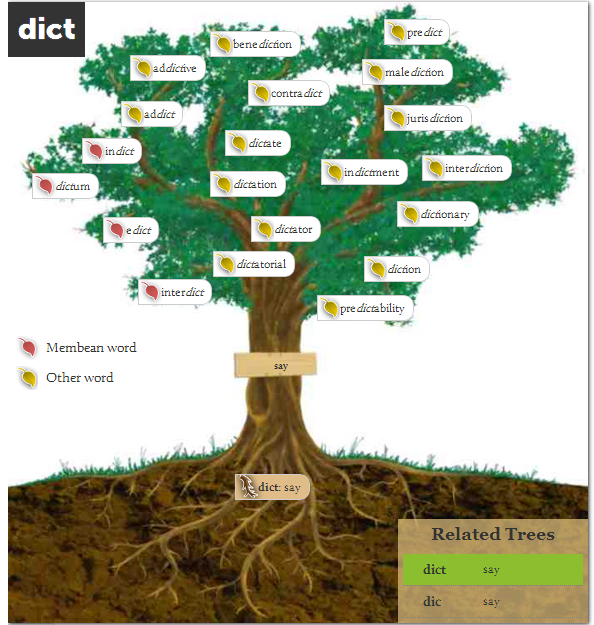

- Word trees. A popular approach to exploring word families is to generate word trees. Websites like Membean.com do a great job of generating these, but it can be equally as good to generate them on a classroom display, or together as a class on the whiteboard (this can be planned, or spontaneous, if the pupils detect some meaningful morphology.

- Making morphemes visible. A lively way to generate ideas is to hold back on the word root, but to instead to share three images that are all represent words connected by their common roots. For instance, what do they follow three images represent?

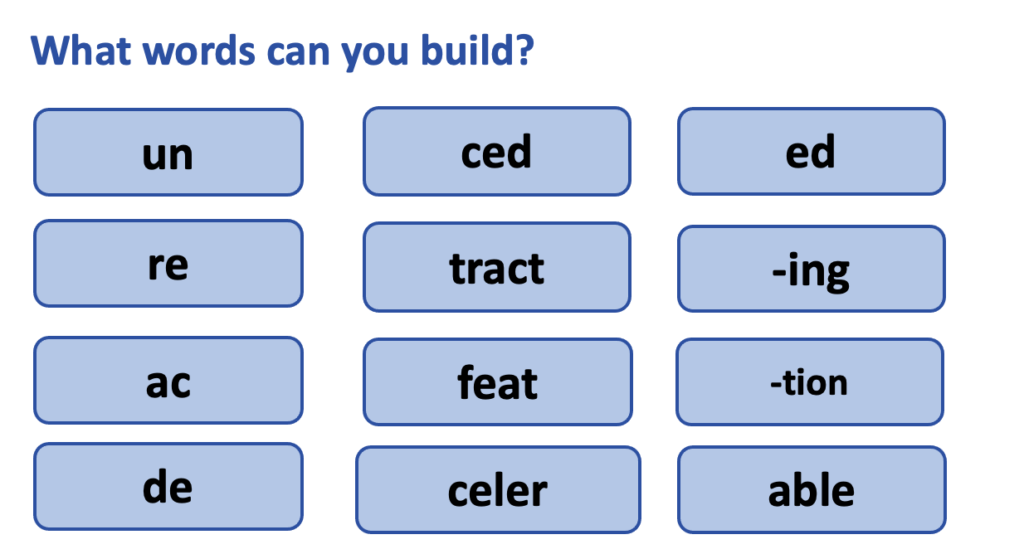

- Word building. For the very youngest of children, all the way up to A level, we can develop vocabulary via word building. It has many variants, but the kernel of the approach it to select prefixes (e.g. ‘un’, ‘re’ or ‘exo’) along with word roots (e.g. ‘tract’, ‘feat’ etc.) and suffixes (‘ed’, ‘ing’ etc.) and encouraging word building. You can even have fun making up some nonsense words!

Related reading:

I have written before on the power of morphology for teaching academic vocabulary:

Thank you for this research and recommendations. I have found the morphological matrix-maker very useful with my third graders. http://www.neilramsden.co.uk/spelling/matrix/

Under the old National Literacy Strategy there was a focus on encouraging pupils to produce their own word webs which taught them the root part of a word and this then led to them being able to decode unfamiliar words. This is a teaching idea which seems to have gone out of fashion but I think it still has value – which is what I am taking from this blog.

Yes – I don’t think it is a new idea (in fact, it is pretty ancient!) but I agree that it can have real value.